“Comfort Women” Then and Now:

Who They Were and Why We Should Remember Them

Who They Were and Why We Should Remember Them

March 2–August 4, 2024

The term “comfort women” refers to the tens to hundreds of thousands of women and girls forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces between 1932 and 1945 in areas under its colonial and wartime command. “Comfort women” is a euphemism and does not describe the ordeals the victims went through. We continue to use the term because of its historical significance—the term was created and used to refer to the women by the Japanese military at the time, and it appears in thousands of military documents created during the war—but we place it in quotation marks to highlight that the term is deceptive and does not reflect the historical reality.

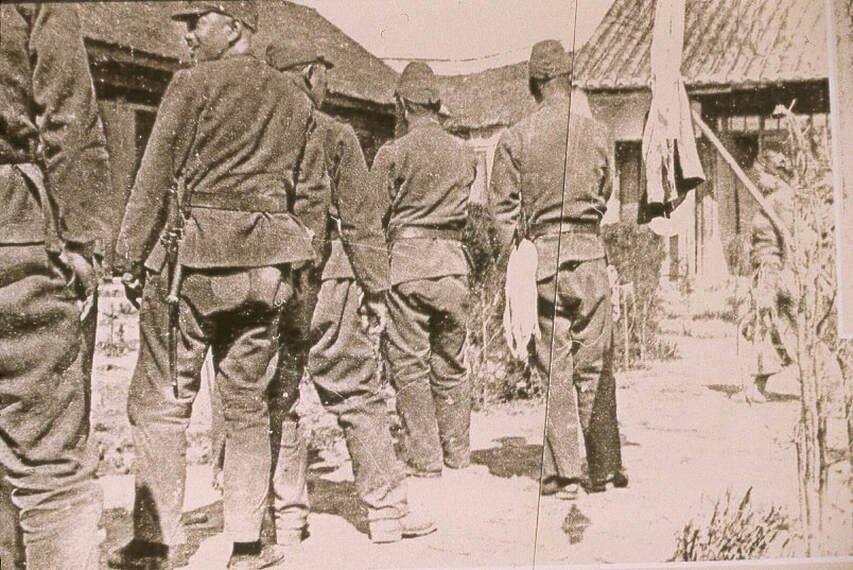

The purpose of setting up the “comfort stations”—in reality, brothels—was to mitigate the local people’s hostility toward the Japanese soldiers for raping local women in the occupied territories and to prevent the risk of venereal diseases and espionage that might occur when the soldiers visited local brothels. Providing sex for soldiers was a deliberate military strategy.

Through the use of force, abductions, and false promises of paid work for the wartime effort, the Japanese military coerced tens to hundreds of thousands of women and girls as young as 12 years old into sex slavery. About 10 percent of these women survived the war. After the war ended in 1945, they went silent due to an immense sense of shame.

After 50 years of silence, the Grandmas (an affectionate term to refer to the survivors) courageously broke their silence in the early 1990s. They began demanding an official apology and legal compensation from the Japanese government. Some became leaders of the redress movement and made an international impact.

The purpose of setting up the “comfort stations”—in reality, brothels—was to mitigate the local people’s hostility toward the Japanese soldiers for raping local women in the occupied territories and to prevent the risk of venereal diseases and espionage that might occur when the soldiers visited local brothels. Providing sex for soldiers was a deliberate military strategy.

Through the use of force, abductions, and false promises of paid work for the wartime effort, the Japanese military coerced tens to hundreds of thousands of women and girls as young as 12 years old into sex slavery. About 10 percent of these women survived the war. After the war ended in 1945, they went silent due to an immense sense of shame.

After 50 years of silence, the Grandmas (an affectionate term to refer to the survivors) courageously broke their silence in the early 1990s. They began demanding an official apology and legal compensation from the Japanese government. Some became leaders of the redress movement and made an international impact.

1895–1945

After winning the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japan colonized Taiwan and Korea and continued to invade China and Southeast Asia. By 1942, Japan had become the largest empire in history.

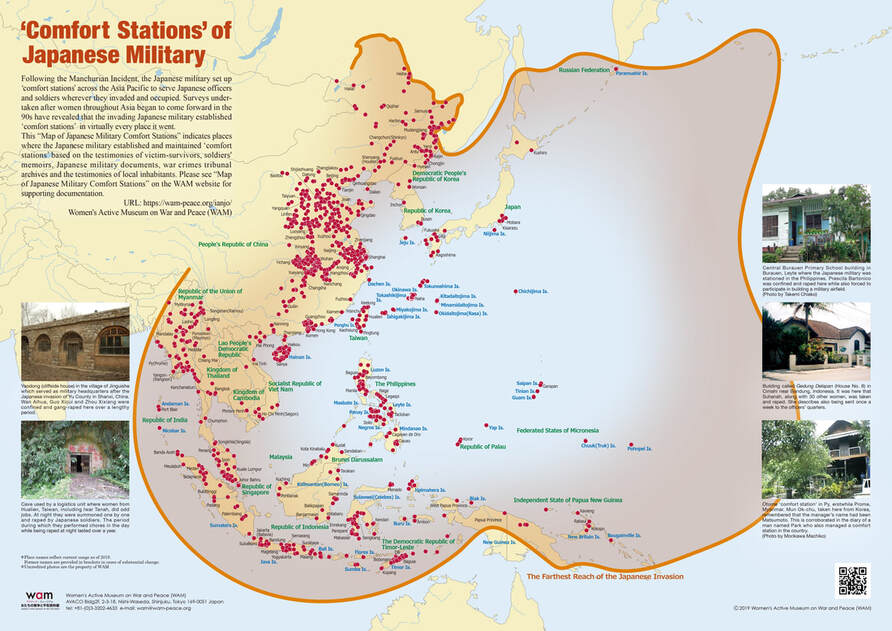

Historians estimate the number of victims ranges from at least 50,000 up to 400,000 women and girls from Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, and East Timor, as well as countries with military and civilian presence in the regions, such as the Netherlands, Germany, France, United Kingdom, and the United States.

The dots on the map represent the locations of the “comfort stations.” The areas in which they were set up match with Japan’s war zones and occupied territories.

Women were confined in remote foreign territories under brutal conditions and forced to have sex with as many as 40 soldiers a day. The women suffered severely from physical and psychological abuse, unwanted pregnancies, and forced abortion. Those who tried to escape were mercilessly killed in front of other women as a warning to them.

|

This document from Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs during the war shows how the Japanese military could transport “comfort women” overseas without needing passports.

As a result of the Japanese military’s willful destruction of documents at the end of the war, no one knows precisely how many girls and women were victimized, but surviving documents and testimonies of victims and witnesses demonstrate the existence and the scale of the sex slavery system. |

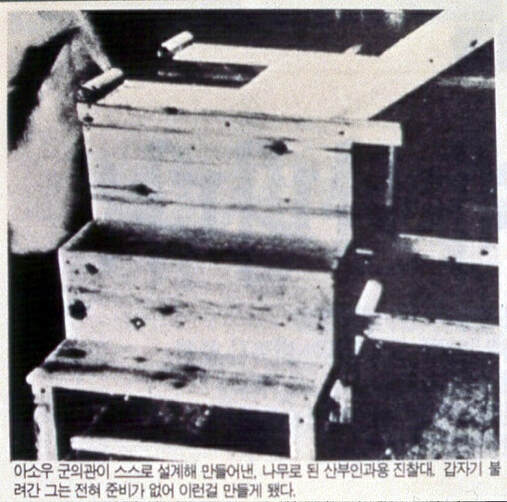

Military doctors regularly examined women for venereal diseases, but other diseases were not treated. One Japanese military document refers to the “comfort stations” as “public toilets.” The Japanese military built the stations and established rules and regulations, including visiting times and fees.

|

Explanation of Japan’s aggression into Asia and the Nanjing Massacre, including testimonies of a “comfort woman” survivor and witnesses.

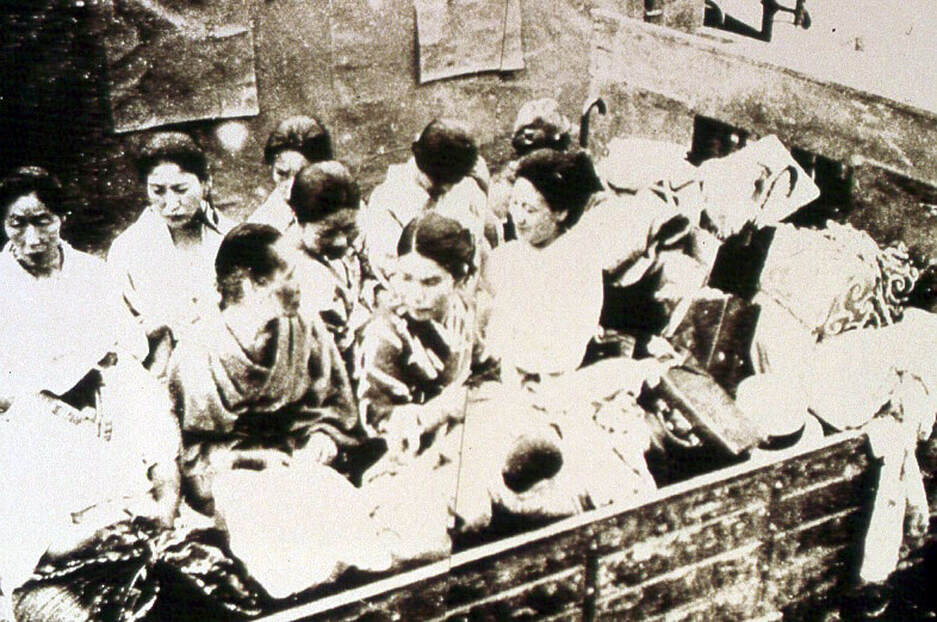

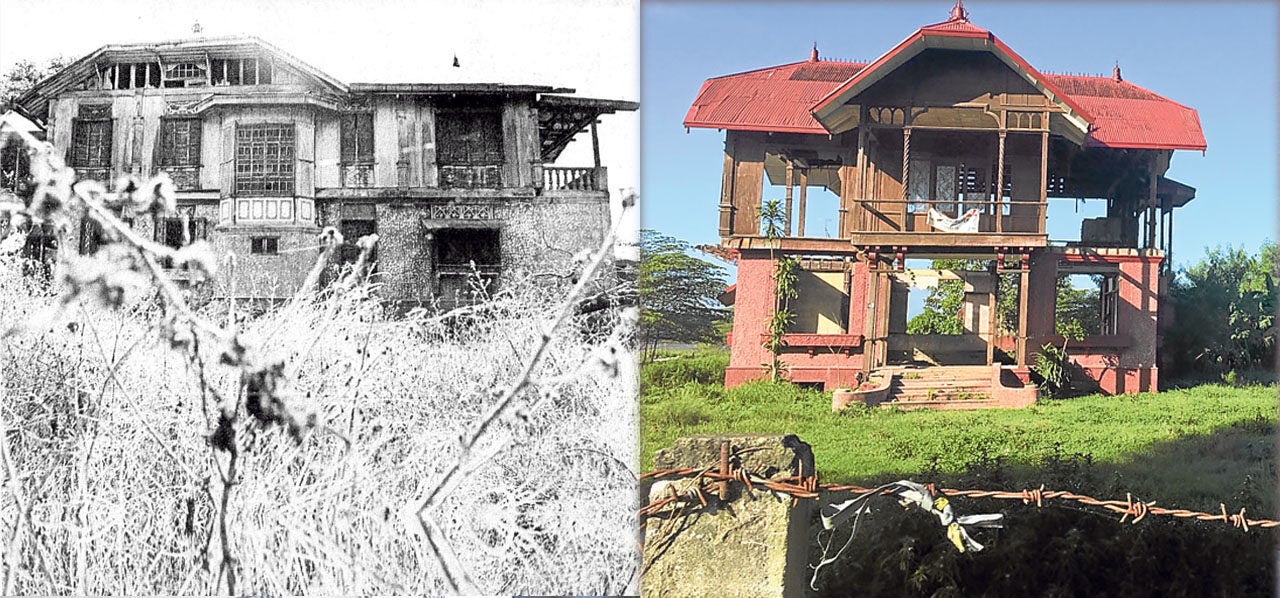

The pregnant woThe pregnant woman (Young-shim Park from North Korea)in the photo of the “comfort women” rescued in China (photo above) had been enslaved at the Lijixiang Comfort Station (lower left photo). Park testified at the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery in Tokyo, Japan, in 2000, and she visited and identified the Nanjing site in 2003.

Near the end of the war, the Japanese military not only destroyed documents but also massacred “comfort women” to cover up the crime. Only a small number of women survived the war, and the lucky ones were found by the Allied forces and sent back home. Some women chose to stay where they had been abandoned out of shame and never returned home.

THE SURVIVORS

Seo-woon Chung, South Korea (1924–2004)

Yong-soo Lee, South Korea (1928–)

Bok-dong Kim, South Korea (1926–2019)

Ines Magalhaes Goncalves, East Timor (1930–)

Japanese troops came to Ines Magalhaes Goncalves’s village around 1943. She was forced to build a road during the day and have sex with Japanese soldiers at night. She said, “I was still a child and did not have periods yet.” She had to have sex with four to eight soldiers a night and became so ill that she could no longer serve as a “comfort woman.” While she was at the “comfort station,” she gave birth to a girl, but the military took the child away when the troops had to leave. She felt ashamed her whole life and is still waiting for an apology from the Japanese government.

Soo-dan Lee, Korean in China (1922–2016)

Soo-dan Lee was 18 when she was sent to China to serve as a “comfort woman” for five years. After the war, she remained in the remote area of China where the Japanese military abandoned her. She lost her mother tongue over several decades, and she never was able to return to Korea. At the end of her life, she became attached to a baby doll, giving it tremendous care and love as if it were a real baby. Photographer Se-hong Ahn of the JUJU Project visited her several times to take photos of her.

Suharti, Indonesia (1927–2018)

In 1942, Japan invaded Indonesia, then a Dutch colony. Suharti was born in Blitar, East Java. In 1944, the Japanese Army ordered the village officers to register all girls and boys of 15 years or older. The village chief told Suharti’s father she would be educated in another city and work in an office. Despite her father’s strong opposition, Suharti was shipped to Balikpapan, where she was enslaved for six months. She was interviewed by Koichi Kimura and Eka Hindrati in 1996. (Photo by Meichi Sitorus)