Dr. Kent Kirkton, Charles Bowden, Dr. José Luis Benavides, and Julián Cardona

Dr. Kent Kirkton, Charles Bowden, Dr. José Luis Benavides, and Julián Cardona

Mexican journalist Julián Cardona (1960–2020) had the rare ability to see beyond the fictional reality created and publicized by powerful social actors—including the press. His lens was always documenting places and people based on his wide-angle and long view of the world. Very few journalists working with a camera have his encyclopedic knowledge of history and his strong critical-thinking skills to guide their journalistic work. Julián never fell into the trap of the immediacy of news.

In 2005, summing up what he saw evolving after Nafta was put in place, Julián observed, “Some were saying that History had ended and announced the arrival of a new Golden Age. Now, more than a decade later, we hear that the world is flat. That day-by-day, people the world over are rising to the next level in the expanding global economy. If that is true, then we need some name for these other things that have broken out since borders opened up for trade and goods and slammed shut to people: child labor, sweatshops, human trafficking, ever-increasing quantities of drugs, explosive violence and endless streams of migrants. The reinvention of slavery.”

He cared deeply about “these other things” that enslaved the people at the bottom, and he gave himself photo assignments that nobody else thought of or dared to try. He was particularly proud of the photographs he captured undercover inside a maquiladora—the Mexican elites and their foreign partners have never wanted people to see what was going on there, and no paparazzi hid in wait to take photos of these exploited workers. Unfortunately, these photos of economic violence against working women caused less commotion than the photos of dead women that appeared in the controversial book he helped edit with Chares Bowden, Juárez the Laboratory of Our Future.

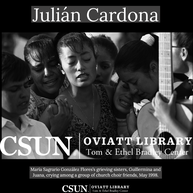

He was also proud of the work he did documenting the final years of Voces sin Eco, a family collective demanding justice for their killed and disappeared daughters. A powerful photograph published in the book and part of the exhibition showed María Sagrario González Flores’s grieving sisters, Guillermina and Juana, crying among a group of church choir friends. The image captures their grief, despair, and determination to seek out justice, which they achieved eventually through their activism.

This and other powerful photographs were part of the book Exodus, published in 2008. Exodus is by far the best visual and written account of the impact of Nafta on Mexico. It chronicled the forced displacement and exodus of millions of poor people. In the book, Julián astutely viewed these economic exiles as macehuales—laborers who were given as slaves to sustain the Aztec empire’s elites—but now given as a slave force to a different empire, the United States.

In 2014, an exhibition of images from the book opened at the Museum of Social Justice, thanks to the almost inexhaustible persuasive powers of Dr. Kent Kirkton, founder of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center and member of the Museum’s advisory board. Dr. Kirkton convinced Julián to have the exhibition at the Museum, which Julián visited while he was working at the Center to organize his photo collection. Julián loved to interact with the public who visited the exhibition, including as they identified places and situations that they had themselves been in during their own exodus journeys. Julián conceived of the people in his photos as the parents of the “new Americans.” He wanted to capture the hardships of their journey and their labor, as well as the size of their dreams.

Our only consolation in Julián's untimely departure is that he was able to finish a manuscript for a new book in collaboration with artist Alice Briggs, Abecedario de Juárez, to be published by UT Press in 2021. This time, Julián used the power of the written word to tell us stories about a complex reality that he recently described as “unphotographable.” The book will introduce us to a new lexicon that emerged in Juárez and that, like his photographs and Alice’s artwork, will help us understand the reality of the only industry that has experienced sustained growth in this border city and in all Mexico during the last two decades: crime.

The Exodus exhibition turned Julián into a friend of all the people that are part of the Museum—docents, board members, curators, donors, affiliated scholars. He was willing to teach us all about Juárez, a city he loved deeply and helped us understand and love as well. All his family at the Museum will miss him infinitely. He made the world a better place with his visual and written work, and he certainly embodied the spirit of what the Museum of Social Justice aims to accomplish—to tell the neglected stories of the people without history.

Dr. José Luis Benavides

Board Member of the Museum of Social Justice and Director of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center

In 2005, summing up what he saw evolving after Nafta was put in place, Julián observed, “Some were saying that History had ended and announced the arrival of a new Golden Age. Now, more than a decade later, we hear that the world is flat. That day-by-day, people the world over are rising to the next level in the expanding global economy. If that is true, then we need some name for these other things that have broken out since borders opened up for trade and goods and slammed shut to people: child labor, sweatshops, human trafficking, ever-increasing quantities of drugs, explosive violence and endless streams of migrants. The reinvention of slavery.”

He cared deeply about “these other things” that enslaved the people at the bottom, and he gave himself photo assignments that nobody else thought of or dared to try. He was particularly proud of the photographs he captured undercover inside a maquiladora—the Mexican elites and their foreign partners have never wanted people to see what was going on there, and no paparazzi hid in wait to take photos of these exploited workers. Unfortunately, these photos of economic violence against working women caused less commotion than the photos of dead women that appeared in the controversial book he helped edit with Chares Bowden, Juárez the Laboratory of Our Future.

He was also proud of the work he did documenting the final years of Voces sin Eco, a family collective demanding justice for their killed and disappeared daughters. A powerful photograph published in the book and part of the exhibition showed María Sagrario González Flores’s grieving sisters, Guillermina and Juana, crying among a group of church choir friends. The image captures their grief, despair, and determination to seek out justice, which they achieved eventually through their activism.

This and other powerful photographs were part of the book Exodus, published in 2008. Exodus is by far the best visual and written account of the impact of Nafta on Mexico. It chronicled the forced displacement and exodus of millions of poor people. In the book, Julián astutely viewed these economic exiles as macehuales—laborers who were given as slaves to sustain the Aztec empire’s elites—but now given as a slave force to a different empire, the United States.

In 2014, an exhibition of images from the book opened at the Museum of Social Justice, thanks to the almost inexhaustible persuasive powers of Dr. Kent Kirkton, founder of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center and member of the Museum’s advisory board. Dr. Kirkton convinced Julián to have the exhibition at the Museum, which Julián visited while he was working at the Center to organize his photo collection. Julián loved to interact with the public who visited the exhibition, including as they identified places and situations that they had themselves been in during their own exodus journeys. Julián conceived of the people in his photos as the parents of the “new Americans.” He wanted to capture the hardships of their journey and their labor, as well as the size of their dreams.

Our only consolation in Julián's untimely departure is that he was able to finish a manuscript for a new book in collaboration with artist Alice Briggs, Abecedario de Juárez, to be published by UT Press in 2021. This time, Julián used the power of the written word to tell us stories about a complex reality that he recently described as “unphotographable.” The book will introduce us to a new lexicon that emerged in Juárez and that, like his photographs and Alice’s artwork, will help us understand the reality of the only industry that has experienced sustained growth in this border city and in all Mexico during the last two decades: crime.

The Exodus exhibition turned Julián into a friend of all the people that are part of the Museum—docents, board members, curators, donors, affiliated scholars. He was willing to teach us all about Juárez, a city he loved deeply and helped us understand and love as well. All his family at the Museum will miss him infinitely. He made the world a better place with his visual and written work, and he certainly embodied the spirit of what the Museum of Social Justice aims to accomplish—to tell the neglected stories of the people without history.

Dr. José Luis Benavides

Board Member of the Museum of Social Justice and Director of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center