La Plaza: A Center of Injustice and Transformation in Los Angeles

March 3–August 6, 2023

March 3–August 6, 2023

In celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Museum of Social Justice’s inaugural exhibition, Angels on the Plaza, this survey exhibition explores La Plaza de Los Ángeles, the birthplace of the city, as a center of injustice and transformation. From its beginning, La Plaza has been a hub of diversity, strife, and social and political change. It has been a place of contradiction. It has been a place where American Indians; African, Mexican, and Spanish settlers; Chinese and Italian immigrants; and Anglo-Americans lived and worked among one another.

This diversity often led to discord and unity at La Plaza. It was a place of injustices where racism led to the deportation of Mexican residents, the massacre of Chinese residents, auctions of American Indians, and heavy police surveillance of marginalized people and activists. Yet, it was also a place of transformation, where the city’s free speech area and first integrated drinking fountain were located. Immigrants could access extensive social services through La Plaza United Methodist Church and La Plaza Community Center. Worker unions formed here; civil and labor rights campaigns were fought here; and both exiled and native revolutionaries sought social and political change through art, writing, and demonstrations here. Throughout its history, La Plaza has been a place of protest, a place to fight against the city’s inequalities and seek justice for all its residents. Two centuries later, this legacy continues, as Angelenos fight for change among La Plaza’s historical sites and outside the shops and restaurants of Olvera Street, accompanied by the music and dance of the city’s residents.

This project was made possible through the support of and with contributions by the Museum of Social Justice, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, and the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles.

This diversity often led to discord and unity at La Plaza. It was a place of injustices where racism led to the deportation of Mexican residents, the massacre of Chinese residents, auctions of American Indians, and heavy police surveillance of marginalized people and activists. Yet, it was also a place of transformation, where the city’s free speech area and first integrated drinking fountain were located. Immigrants could access extensive social services through La Plaza United Methodist Church and La Plaza Community Center. Worker unions formed here; civil and labor rights campaigns were fought here; and both exiled and native revolutionaries sought social and political change through art, writing, and demonstrations here. Throughout its history, La Plaza has been a place of protest, a place to fight against the city’s inequalities and seek justice for all its residents. Two centuries later, this legacy continues, as Angelenos fight for change among La Plaza’s historical sites and outside the shops and restaurants of Olvera Street, accompanied by the music and dance of the city’s residents.

This project was made possible through the support of and with contributions by the Museum of Social Justice, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, and the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles.

Slavery in Los Angeles:

The Auctioning of American Indians, 1850–1870

The California State Legislature passed the 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, enabling White people to legally enslave American Indian people. Moreover, in August 1850, the common council of Los Angeles passed a set of policies authorizing the city marshal to arrest “vagrant” American Indians and auction them for a week of labor.

As a result, American Indians were caught in a cycle of repeated arrest and forced labor. Vineyard owners and ranchers who relied on cheap American Indian labor often gave workers liquor in lieu of pay. This led American Indian workers, who gathered on the weekend at Calle de los Negros (now Los Angeles Street) at the edge of La Plaza, to be subject to arrest for public intoxication and vagrancy. The city marshal and deputies conducted sweeps for American Indians to arrest, and held them in the jail’s open-air enclosure. On Monday morning, they were auctioned at a slave market held at the Downey Block, a building on a site where the Spring Street Courthouse now stands. Vineyard owners and ranchers bid up to $4 to pay off the arrestees’ bail and then forced them to one week of labor. Workers might receive $1 to $2 in pay for the week, often in the form of liquor, leading to another cycle of arrest and servitude. For every fine paid, the marshal received $1, and his deputies shared 12.5¢. The rest of the auction proceeds went to the city, becoming a lucrative source of revenue—second only to license fees for drinking and gambling establishments.

In 1870, when the labor of American Indians was no longer essential to the Los Angeles economy, the auctions came to an end. The auctions stand as one glaring instance of how White Californian society abused and discriminated against American Indians. This was a form of physical and economic violence against Indigenous people, who were denied the rights of citizenship and exploited by Whites. As a result of the cycle of brutality and forced labor, between 1850 and 1870, the population of American Indians in Los Angeles plummeted from 3,693 to 219 people.

As a result, American Indians were caught in a cycle of repeated arrest and forced labor. Vineyard owners and ranchers who relied on cheap American Indian labor often gave workers liquor in lieu of pay. This led American Indian workers, who gathered on the weekend at Calle de los Negros (now Los Angeles Street) at the edge of La Plaza, to be subject to arrest for public intoxication and vagrancy. The city marshal and deputies conducted sweeps for American Indians to arrest, and held them in the jail’s open-air enclosure. On Monday morning, they were auctioned at a slave market held at the Downey Block, a building on a site where the Spring Street Courthouse now stands. Vineyard owners and ranchers bid up to $4 to pay off the arrestees’ bail and then forced them to one week of labor. Workers might receive $1 to $2 in pay for the week, often in the form of liquor, leading to another cycle of arrest and servitude. For every fine paid, the marshal received $1, and his deputies shared 12.5¢. The rest of the auction proceeds went to the city, becoming a lucrative source of revenue—second only to license fees for drinking and gambling establishments.

In 1870, when the labor of American Indians was no longer essential to the Los Angeles economy, the auctions came to an end. The auctions stand as one glaring instance of how White Californian society abused and discriminated against American Indians. This was a form of physical and economic violence against Indigenous people, who were denied the rights of citizenship and exploited by Whites. As a result of the cycle of brutality and forced labor, between 1850 and 1870, the population of American Indians in Los Angeles plummeted from 3,693 to 219 people.

|

The Old Downey Block

George Washington Hazard Approximately 1897–1904 Photographic reproduction Courtesy of the Ernest Márquez Collection, Huntington Library |

Calle de los Negros Stagecoach

Circa 1870 Photographic reproduction Courtesy of the Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library |

Chinese Massacre of 1871

In the 1870s, anti-Chinese sentiment in Los Angeles was high. The Chinese population made up 172 of the 5,728 city residents, about three percent of the population. More than half of the Chinese community lived in the adobes along Calle de los Negros (now Los Angeles Street), which was in the central part of the Chinatown of that era, and which is now the location of the Chinese American Museum.

On October 24, 1871, tensions were high because of a feud between two Chinese benevolent associations over a young Chinese woman's kidnapping. A shootout broke out that injured a police officer and killed Robert Thompson, a saloon owner. The shooters hid in the Coronel family adobe with terrified Chinese residents. With news of the shooting, a mob of 500 non-Chinese men formed, and the sheriff ordered them to stop any Chinese people from escaping, even if that meant shooting them. The crowd shot three men and dragged 15 others to makeshift gallows at nearby locations including a corral and a wagon shop.

The following day, 17 bodies were laid out in the jail yard. Another victim had been buried the night before. Out of the victims, only one had participated in the original shootout. The others were stopped trying to escape out the back of the adobe. Ten percent of the Chinese population was killed, including the well-known physician Dr. Chee Long "Gene" Tong.

Although hundreds participated in the killings, only eight men were convicted of manslaughter. Their convictions were overturned on appeal, and they were never retried. Within a short time, the massacre was forgotten, and anti-Chinese sentiment grew even stronger.

On October 24, 1871, tensions were high because of a feud between two Chinese benevolent associations over a young Chinese woman's kidnapping. A shootout broke out that injured a police officer and killed Robert Thompson, a saloon owner. The shooters hid in the Coronel family adobe with terrified Chinese residents. With news of the shooting, a mob of 500 non-Chinese men formed, and the sheriff ordered them to stop any Chinese people from escaping, even if that meant shooting them. The crowd shot three men and dragged 15 others to makeshift gallows at nearby locations including a corral and a wagon shop.

The following day, 17 bodies were laid out in the jail yard. Another victim had been buried the night before. Out of the victims, only one had participated in the original shootout. The others were stopped trying to escape out the back of the adobe. Ten percent of the Chinese population was killed, including the well-known physician Dr. Chee Long "Gene" Tong.

Although hundreds participated in the killings, only eight men were convicted of manslaughter. Their convictions were overturned on appeal, and they were never retried. Within a short time, the massacre was forgotten, and anti-Chinese sentiment grew even stronger.

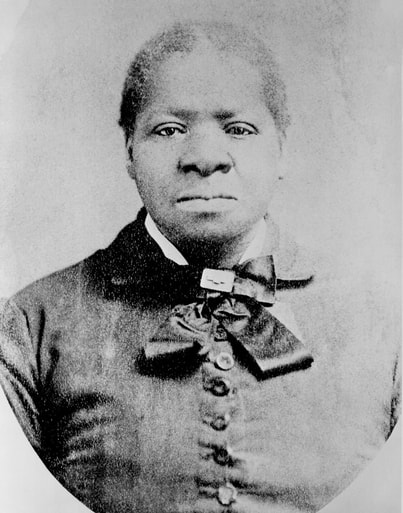

Women of La Plaza

Women in Los Angeles often led initiatives at and around La Plaza. Their philanthropy and dedication to social change aimed to give Angelenos opportunities for a better life.

One of the earliest examples of women taking on this role was Bridget “Biddy” Mason. In 1851, she arrived in San Bernardino, in California (a free state), as an enslaved person owned by Robert Smith. Mason fought for her freedom in court and won it in 1856. Living in Los Angeles, Mason saved her earnings as a nurse and midwife to buy a homestead on Spring and Third Streets, one of the first African American women to purchase property in the city. Additionally, she created a daycare center for working parents and a relief fund for families experiencing hardship, and she financed the First African Methodist Episcopal Church. Mason spoke fluent Spanish and was well known and respected at La Plaza, where she conducted business and dined at the Pico House. After Mason passed away in 1891, her property passed down to her heirs. It is now home to the Biddy Mason Memorial Park.

From the early 1900s, the women of La Plaza United Methodist Church advocated for the rights of the poor, working class, and immigrant residents of Los Angeles through social services and community programs. La Plaza Community Center was central to the church’s work to promote socioeconomic and health-related equality for all Los Angeles citizens. The center was home to a medical and dental clinic, an employment office, a daycare and kindergarten, trade classes, and most notably, the city's first integrated drinking fountain, from which anyone, of any race, could freely drink. The drinking fountain stood as a symbol of unity. The services provided through La Plaza Community Center were critical at a time when many of the city’s facilities were segregated. The center’s programs were also supported by the Goodwill Store, founded by church member Katherine Higgins in 1918. You can view the church’s permanent exhibition about the history of La Plaza United Methodist Church and La Plaza Community Center upstairs in the narthex

One of the earliest examples of women taking on this role was Bridget “Biddy” Mason. In 1851, she arrived in San Bernardino, in California (a free state), as an enslaved person owned by Robert Smith. Mason fought for her freedom in court and won it in 1856. Living in Los Angeles, Mason saved her earnings as a nurse and midwife to buy a homestead on Spring and Third Streets, one of the first African American women to purchase property in the city. Additionally, she created a daycare center for working parents and a relief fund for families experiencing hardship, and she financed the First African Methodist Episcopal Church. Mason spoke fluent Spanish and was well known and respected at La Plaza, where she conducted business and dined at the Pico House. After Mason passed away in 1891, her property passed down to her heirs. It is now home to the Biddy Mason Memorial Park.

From the early 1900s, the women of La Plaza United Methodist Church advocated for the rights of the poor, working class, and immigrant residents of Los Angeles through social services and community programs. La Plaza Community Center was central to the church’s work to promote socioeconomic and health-related equality for all Los Angeles citizens. The center was home to a medical and dental clinic, an employment office, a daycare and kindergarten, trade classes, and most notably, the city's first integrated drinking fountain, from which anyone, of any race, could freely drink. The drinking fountain stood as a symbol of unity. The services provided through La Plaza Community Center were critical at a time when many of the city’s facilities were segregated. The center’s programs were also supported by the Goodwill Store, founded by church member Katherine Higgins in 1918. You can view the church’s permanent exhibition about the history of La Plaza United Methodist Church and La Plaza Community Center upstairs in the narthex

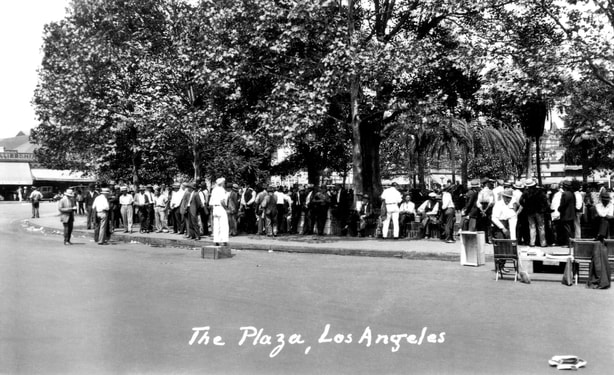

Los Angeles's Free Speech Area

During the Progressive Era (1890–1920), the United States faced a time of extreme change as Progressives advocated for causes such as the end of child labor, women’s suffrage, eight-hour workdays, and safer working conditions. At the time, the average workweek was twelve hours a day, six days a week, with low wages. The fight for better working conditions and pay took place throughout the nation, often leading to violent confrontations between workers and employers.

To prevent confrontations like this from occurring in Los Angeles, the city council passed a free speech ordinance in 1909. It prohibited public speech on all city streets and private properties, except at La Plaza. The law was urged by local business owners who were determined to fight the growth of radical labor and socialist sentiment, particularly that of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), by containing free speech in one area that was far enough from their operations in the city’s business district but close to the police department and city and county jails.

As the city expanded, La Plaza redefined itself as the center for immigrant and working-class communities and a space for organizing. While initially the free speech area was meant to isolate radical labor rhetoric, it ended up serving as a forum for radical and revolutionary groups and their supporters, like the members of the Partido Liberal Mexicano and the IWW’s Wobblies, who actively opposed the LA Times’s and the Merchants and Manufacturers Association’s policies that weakened unions.

To prevent confrontations like this from occurring in Los Angeles, the city council passed a free speech ordinance in 1909. It prohibited public speech on all city streets and private properties, except at La Plaza. The law was urged by local business owners who were determined to fight the growth of radical labor and socialist sentiment, particularly that of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), by containing free speech in one area that was far enough from their operations in the city’s business district but close to the police department and city and county jails.

As the city expanded, La Plaza redefined itself as the center for immigrant and working-class communities and a space for organizing. While initially the free speech area was meant to isolate radical labor rhetoric, it ended up serving as a forum for radical and revolutionary groups and their supporters, like the members of the Partido Liberal Mexicano and the IWW’s Wobblies, who actively opposed the LA Times’s and the Merchants and Manufacturers Association’s policies that weakened unions.

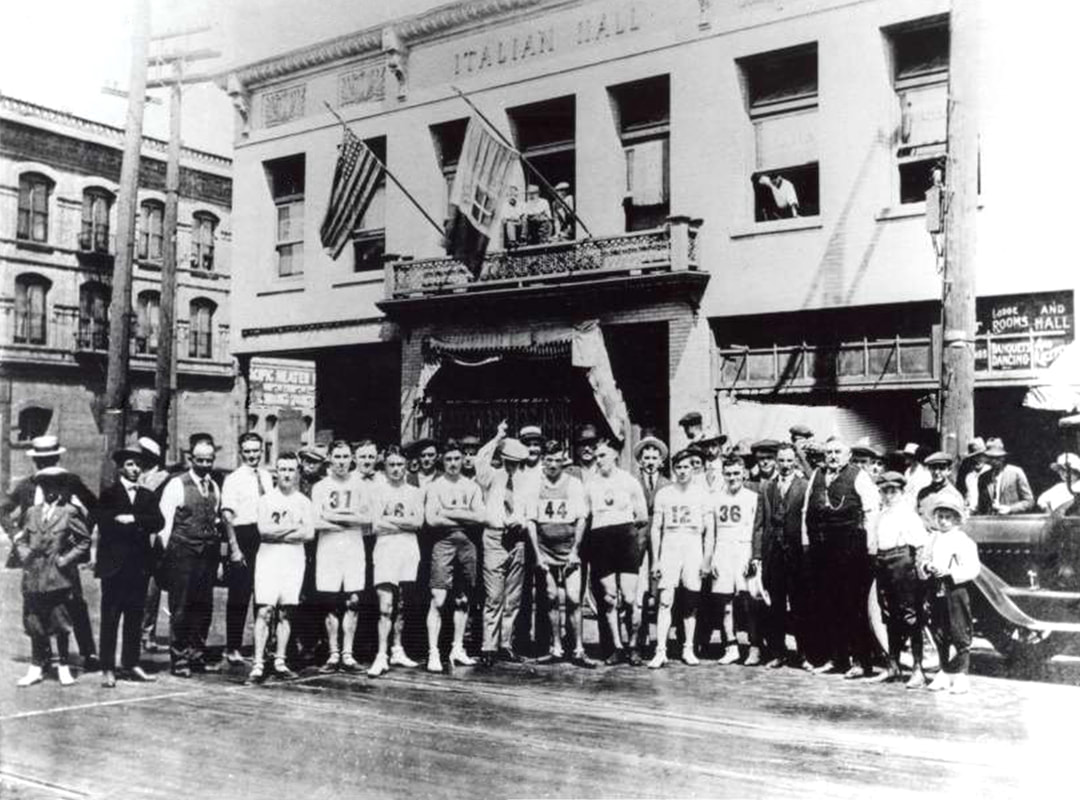

The Italian Hall

Between 1890 and 1950, most Italian immigrants arriving in the US were from Italy’s southern regions. They faced scorn because of anti-Catholic sentiment among most Anglo-American residents of Los Angeles during that time. However, La Plaza, with its Mexican community that observed similar Catholic rituals, was a welcoming place for Italian immigrants to settle. They attended mass, lived, and worked at La Plaza and in the surrounding area. Italian businesses such as bakeries, markets, and cigar shops served as community gathering places for Italian residents.

In 1907, encouraged by Frank Arconti, Marie Harmmel built the Italian Hall on Main Street to serve as the central gathering place for Italians at La Plaza. It was where Italian immigrants went for employment and housing opportunities upon arriving in Los Angeles and where cultural, social, and political events took place. The first floor housed numerous Italian-owned businesses. The second floor served as the headquarters for La Societá Garibaldina di Mutua Beneficenza (the Garibaldina Mutual Benefit Society), which provided financial assistance to its members and aided local hospitals and the poor. Il Circolo Operaio Italiano (the Italian Worker’s Club) met at the Italian Hall to organize events such as May Day and weekly socials. The worker’s club also connected the Italian Hall with non-Italian organizations and individuals, such as the International Workers of the World, Russian anarchist Emma Goldman, and the Flores Magón brothers of the Partido Liberal Mexicano.

In the 1930s, the Italian population outgrew the hall. As a result, it has played different roles over the years, most notably as the location of the América Tropical mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros. Today the Italian Hall is home to the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles.

In 1907, encouraged by Frank Arconti, Marie Harmmel built the Italian Hall on Main Street to serve as the central gathering place for Italians at La Plaza. It was where Italian immigrants went for employment and housing opportunities upon arriving in Los Angeles and where cultural, social, and political events took place. The first floor housed numerous Italian-owned businesses. The second floor served as the headquarters for La Societá Garibaldina di Mutua Beneficenza (the Garibaldina Mutual Benefit Society), which provided financial assistance to its members and aided local hospitals and the poor. Il Circolo Operaio Italiano (the Italian Worker’s Club) met at the Italian Hall to organize events such as May Day and weekly socials. The worker’s club also connected the Italian Hall with non-Italian organizations and individuals, such as the International Workers of the World, Russian anarchist Emma Goldman, and the Flores Magón brothers of the Partido Liberal Mexicano.

In the 1930s, the Italian population outgrew the hall. As a result, it has played different roles over the years, most notably as the location of the América Tropical mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros. Today the Italian Hall is home to the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles.

|

Il Circolo Operaio Italiano (the Italian Worker’s Club) Footrace in Front of the Italian Hall

1917 Photographic reproduction Courtesy of the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles |

Communist Rally at La Plaza

Harry Quillen Date unknown Photographic reproduction Courtesy of the Harry Quillen Collection, Los Angeles Public Library |

Industrial Workers of the World and Partido Liberal Mexicano

Members and supporters of many radical and revolutionary factions gathered at La Plaza, most notably the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM).

Formed in 1905, the IWW was the only national labor-based organization at the time that sustained efforts to organize all workers and granted membership to women and other groups that were often excluded from unions. IWW members, known as Wobblies, called for direct action and mass strikes to achieve their goal of a single industrial union of workers. Capitalists and city officials used any tactic necessary, even violence, to stop the political actions, which were often carried out at La Plaza.

PLM founder Ricardo Flores Magón settled in Los Angeles in 1907, after he was exiled from Mexico for calling for the complete overhaul of Mexico’s social, political, and economic systems. He made Los Angeles the headquarters of the PLM until 1919. He knew the importance of La Plaza and made it his forum to rally the consciousness of Mexican and Mexican American workers. He believed that injustice could only be corrected with direct action. Additionally, he used the PLM’s bilingual weekly newspapers, Revolución (1907–1908) and Regeneración (1910–1918), to report on Mexico’s political and economic crisis, US social problems—such as the penal system, the hardships faced by Mexican workers, child labor, and the denial of voting rights to people in large segments of society—and the antiunion practices of the city. Through this reporting, Flores Magón and the PLM sought to spark action.

The radical writings and rallies brought the PLM to the attention of the local police. From 1911 to 1917, Flores Magón was arrested multiple times. He was ultimately sentenced to 20 years in prison for violating the Espionage Act; he died in prison in 1922 at 48.

Formed in 1905, the IWW was the only national labor-based organization at the time that sustained efforts to organize all workers and granted membership to women and other groups that were often excluded from unions. IWW members, known as Wobblies, called for direct action and mass strikes to achieve their goal of a single industrial union of workers. Capitalists and city officials used any tactic necessary, even violence, to stop the political actions, which were often carried out at La Plaza.

PLM founder Ricardo Flores Magón settled in Los Angeles in 1907, after he was exiled from Mexico for calling for the complete overhaul of Mexico’s social, political, and economic systems. He made Los Angeles the headquarters of the PLM until 1919. He knew the importance of La Plaza and made it his forum to rally the consciousness of Mexican and Mexican American workers. He believed that injustice could only be corrected with direct action. Additionally, he used the PLM’s bilingual weekly newspapers, Revolución (1907–1908) and Regeneración (1910–1918), to report on Mexico’s political and economic crisis, US social problems—such as the penal system, the hardships faced by Mexican workers, child labor, and the denial of voting rights to people in large segments of society—and the antiunion practices of the city. Through this reporting, Flores Magón and the PLM sought to spark action.

The radical writings and rallies brought the PLM to the attention of the local police. From 1911 to 1917, Flores Magón was arrested multiple times. He was ultimately sentenced to 20 years in prison for violating the Espionage Act; he died in prison in 1922 at 48.

|

IWW General Defense Committee, Local No. 4

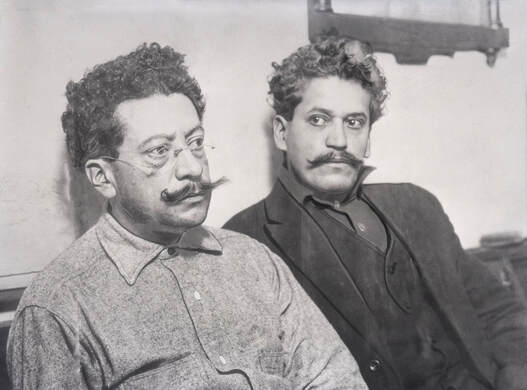

Harry Quillen 1933 Photographic Reproduction Courtesy of the Harry Quillen Collection, Los Angeles Public Library Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón at the Los Angeles Federal Court

1916 Photographic reproduction Courtesy of the UCLA Charles E. Young Research Library Department of Special Collections |

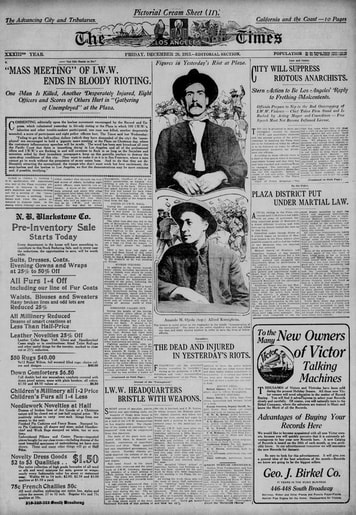

Christmas Day Riot

On December 25, 1913, the Partido Liberal Mexicano and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organized a rally of 500 people at La Plaza to protest the city’s increasing unemployment. The Mexican Wobblies of IWW initiated the demonstration and called for the local government to assist in finding jobs.

The rally began at 2:30 p.m. near the La Plaza fountain. The first speaker, William Owen, an English immigrant and an editor of the anarchist newspaper Regeneración, stood on a box and addressed the crowd in English for over 90 minutes uninterrupted. Then Armando Ojeda spoke in Spanish while standing on a chair. A conflict broke out when police lieutenant Herman Kreige received notice of the event taking place without a permit. He arrived with officers to enforce the city’s public speaking ordinance. While Ojeda was speaking, Kreige ordered him to stop and pulled the chair from underneath him. A man from the crowd protested, and Kreige hit the man in the head with his club. After that, officers began randomly beating people with their clubs. Some people responded by throwing rocks at the officers.

The chaos moved to Sanchez Street, near the Pico House, where police chauffeur Alfred Koenigheim shot IWW member Rafael Adames. The riot continued until 7:30 p.m. In the following days, the city imposed martial law, conducted raids, and searched Mexican men at La Plaza. Police arrested 73 men, 56 of them Mexican.

The riot reinforces the contested views among city officials, the press, and private citizens about La Plaza as a forum for free speech—a contestation heightened when it was used for protests by marginalized groups.

The rally began at 2:30 p.m. near the La Plaza fountain. The first speaker, William Owen, an English immigrant and an editor of the anarchist newspaper Regeneración, stood on a box and addressed the crowd in English for over 90 minutes uninterrupted. Then Armando Ojeda spoke in Spanish while standing on a chair. A conflict broke out when police lieutenant Herman Kreige received notice of the event taking place without a permit. He arrived with officers to enforce the city’s public speaking ordinance. While Ojeda was speaking, Kreige ordered him to stop and pulled the chair from underneath him. A man from the crowd protested, and Kreige hit the man in the head with his club. After that, officers began randomly beating people with their clubs. Some people responded by throwing rocks at the officers.

The chaos moved to Sanchez Street, near the Pico House, where police chauffeur Alfred Koenigheim shot IWW member Rafael Adames. The riot continued until 7:30 p.m. In the following days, the city imposed martial law, conducted raids, and searched Mexican men at La Plaza. Police arrested 73 men, 56 of them Mexican.

The riot reinforces the contested views among city officials, the press, and private citizens about La Plaza as a forum for free speech—a contestation heightened when it was used for protests by marginalized groups.

Survival and Resilience: Mass Deportations and Forced Removals at La Plaza

During the Great Depression (1929–1939), one of the worst economic downturns to affect the US, over a million Mexican and Mexican American citizens were subjected to unconstitutional deportation and removal. US businesses recruited Mexicans and Mexican Americans from the 1880s through the 1920s because they were a reliable and cheap workforce for many industries. Many Mexicans migrated to the US to work in agriculture in the Southwest, Midwest, and South, and in industrial jobs in the Midwest and on the East Coast. During the Great Depression, Mexicans and Mexican Americans were targeted by immigration authorities and illegally removed to Mexico at the order of President Herbert Hoover (1929–1933) as part of a repatriation program. The term repatriation was used as a more palatable euphemism for illegal deportations. Worse yet, 40%–60% of those forcibly removed to Mexico were US citizens.

On February 26, 1931, 400 people visiting La Plaza on a Sunday afternoon were suddenly surrounded by immigration agents and forced to prove their legal residency status. Known as the La Placita raid, this was the first time a major public space in Los Angeles was used to interrogate, arrest, and remove people. La Plaza was a significant cultural hub for Mexicans and Mexican Americans. This raid was used as an example to spread fear among many communities that were deported to Mexico, and traumatized generations. Stories of Mexican and Mexican American survival and resilience are presented to preserve history, establish compassion and understanding, and inspire change for future generations.

Esperanza Sanchez, Associate Curator, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes

Summer Ibarra, Community Support Worker, El Pueblo Historical Monument

On February 26, 1931, 400 people visiting La Plaza on a Sunday afternoon were suddenly surrounded by immigration agents and forced to prove their legal residency status. Known as the La Placita raid, this was the first time a major public space in Los Angeles was used to interrogate, arrest, and remove people. La Plaza was a significant cultural hub for Mexicans and Mexican Americans. This raid was used as an example to spread fear among many communities that were deported to Mexico, and traumatized generations. Stories of Mexican and Mexican American survival and resilience are presented to preserve history, establish compassion and understanding, and inspire change for future generations.

Esperanza Sanchez, Associate Curator, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes

Summer Ibarra, Community Support Worker, El Pueblo Historical Monument

|

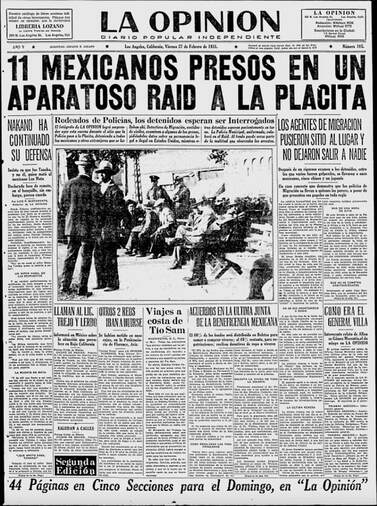

11 Mexicanos presos en un aparatoso raid a la placita (11 Mexicans Arrested in a Massive Raid at La Plaza)

La Opinión February 27, 1931 Newspaper reproduction La Opinión Archive The correspondence between Miguel Venegas and his family in Mexico speaks to common experiences in the US during the 1930s: widespread unemployment, failing businesses, job insecurity, and more. His letters also provide insight and comment on the adverse effects especially felt in the Mexican and Mexican American community. Venegas’s handwritten letter to his brother was accompanied by a clipping from the newspaper La Opinión, which reported on the possibility of a planned raid by the US government. While the detrimental effects of the Great Depression were felt throughout the country, people of color were especially vulnerable.

La Opinión continues to be an influential and top-selling Spanish-language newspaper. Ignacio E. Lozano established La Opinión in 1926 to serve Mexican and Mexican American communities across the country and provided news coverage on Mexico and the US. The importance of La Opinión as a media source during the Great Depression is substantial, as it was one of the few to report on and condemn the unconstitutional deportations and removals of the 1930s. |

Mexicans Returning Home by Train

1932 Herald Examiner photographer Photographic reproduction Courtesy of the Herald Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library Venegas Family Portrait

Miguel Venegas ca. 1930s–1940s and February 17, 1931 Photographic and letter reproductionCourtesy of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, William H. Hannon Library, Loyola Marymount University |

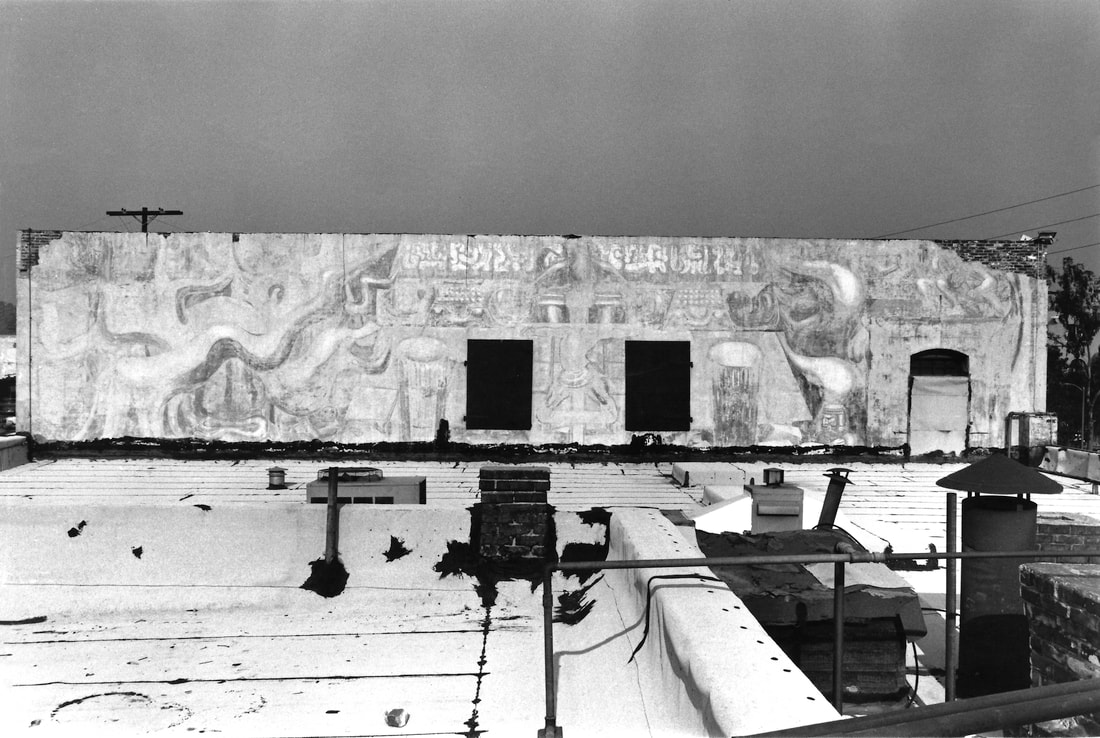

América Tropical

In 1932, La Plaza Art Center commissioned David Alfaro Siqueiros to create an 80-foot-long mural at the rooftop of the Italian Hall, presenting tropical America as a romanticized a land of plenty. What Siqueiros painted instead scandalized the political and cultural establishment of Los Angeles.

On the night of October 9, 1932, América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos (Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism) was revealed to a shocked and insulted crowd. Instead of a serene tropical scene, the mural showed a Pre-Columbian pyramid, in front of which a central Indigenous male figure was shown crucified on a double cross, and which was surrounded by thick, twisted trees. An eagle perched above the body with its talons extended, while two men aimed their rifles at the eagle from the right. While very little of the mural was visible from Olvera Street, the north-facing offices of City Hall had an unobstructed view. The mural reclaimed La Plaza and highlighted the mistreatment of Mexican American workers by Anglo-Americans and their exploitative social structures. It was a powerful political statement on US imperialism in Latin America. It threatened the city’s social order, and it had to go. Just months after the mural was revealed, it was partially whitewashed, and within a matter of years, it was entirely covered over and eventually forgotten.

América Tropical was rediscovered in the late 1960s and 1970s as the whitewash began to peel off. The timing coincided with the rise of the Chicano mural movement, provoking a renewed interest in the work. With the mural’s history and extraordinary content, Chicano activists embraced it as a symbol of their past and present struggles. Today América Tropical continues to be a symbol of protest for oppressed people.

View the mural at the América Tropical Interpretative Center on Olvera Street.

On the night of October 9, 1932, América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos (Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism) was revealed to a shocked and insulted crowd. Instead of a serene tropical scene, the mural showed a Pre-Columbian pyramid, in front of which a central Indigenous male figure was shown crucified on a double cross, and which was surrounded by thick, twisted trees. An eagle perched above the body with its talons extended, while two men aimed their rifles at the eagle from the right. While very little of the mural was visible from Olvera Street, the north-facing offices of City Hall had an unobstructed view. The mural reclaimed La Plaza and highlighted the mistreatment of Mexican American workers by Anglo-Americans and their exploitative social structures. It was a powerful political statement on US imperialism in Latin America. It threatened the city’s social order, and it had to go. Just months after the mural was revealed, it was partially whitewashed, and within a matter of years, it was entirely covered over and eventually forgotten.

América Tropical was rediscovered in the late 1960s and 1970s as the whitewash began to peel off. The timing coincided with the rise of the Chicano mural movement, provoking a renewed interest in the work. With the mural’s history and extraordinary content, Chicano activists embraced it as a symbol of their past and present struggles. Today América Tropical continues to be a symbol of protest for oppressed people.

View the mural at the América Tropical Interpretative Center on Olvera Street.

|

América Tropical Revealed Through the Whitewash

1978 Photographic reproduction Courtesy of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument Collection América Tropical Partially Whitewashed

Circa 1932 Los Angeles Times photographer Photographic reproduction Courtesy of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument Collection |

The Past and Present Meet

The events of injustice and transformation presented here are but a few that have occurred throughout the history of La Plaza. It remains a contested space and a place to fight against the city’s inequalities and seek justice. It continues to serve as a central meeting place for activists and everyday people seeking change. La Plaza is where the past and present meet, where today’s political and social issues intersect with the tourism and cultural events of Olvera Street and the historical sites of El Pueblo de Los Angeles.