DEPORTED VETERANS

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JOSEPH SILVA

FEBRUARY 24–JULY 31, 2022

Foreign-born soldiers have served the United States since the Revolutionary War. The French Marquis de Lafayette, the German Friedrich von Steuben, and the West Indian Alexander Hamilton are just three examples of foreign-born soldiers who fought in George Washington’s Continental Army.

Today, the country has approximately 700,000 foreign-born veterans, 45,000 active members, and each year, 5,000 new immigrants join the military. As of 2018, 17 percent of those foreign-born veterans have not been naturalized.

These soldiers’ dedication to their country matches or surpasses the commitment of the native-born. Their honorable service, however, has been rewarded with dishonorable actions—denial of citizenship, unceremonious deportation, and hardships faced by the veterans and their families.

Since the passage of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act in 1996, the United States has deported thousands of non-citizen military veterans. These veterans are generally childhood arrivals to the United States with legal permanent resident status, who have a criminal record.

This exhibition seeks to create a visual space in which some of these deported veterans not only recover their denied citizenship but also expose the damage inflicted on them by unjust government policies. From Mexico to the Dominican Republic to England to Costa Rica, veterans proudly display the objects that confirm their American citizenship. They want to remind us that their struggle to gain citizen status is a struggle for social justice.

Today, the country has approximately 700,000 foreign-born veterans, 45,000 active members, and each year, 5,000 new immigrants join the military. As of 2018, 17 percent of those foreign-born veterans have not been naturalized.

These soldiers’ dedication to their country matches or surpasses the commitment of the native-born. Their honorable service, however, has been rewarded with dishonorable actions—denial of citizenship, unceremonious deportation, and hardships faced by the veterans and their families.

Since the passage of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act in 1996, the United States has deported thousands of non-citizen military veterans. These veterans are generally childhood arrivals to the United States with legal permanent resident status, who have a criminal record.

This exhibition seeks to create a visual space in which some of these deported veterans not only recover their denied citizenship but also expose the damage inflicted on them by unjust government policies. From Mexico to the Dominican Republic to England to Costa Rica, veterans proudly display the objects that confirm their American citizenship. They want to remind us that their struggle to gain citizen status is a struggle for social justice.

PHOTOGRAPHS

A deported US Army paratrooper with his Corcoran jump boots.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2016.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2016.

|

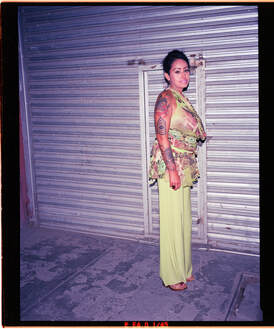

US Marine Corps veteran.

Juarez, Mexico, 2017. |

Repatriated US Army veteran Hector with his deported bride, Yolonda Palacios of Madres Deportadas, looking into the United States on their wedding day.

Playa de Tijuana, Mexico, October 2020. |

A deported veteran and his child at a rest stop in Pedro Brand, a municipality of Santo Domingo, following a long journey into the mountains for a deported veterans’ cookout.

Dominican Republic, August 2019. |

Mauricio, deported US Army Afghanistan War combat veteran, with his daughter at the “Bunker,” the Deported Veteran Support House.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2016.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2016.

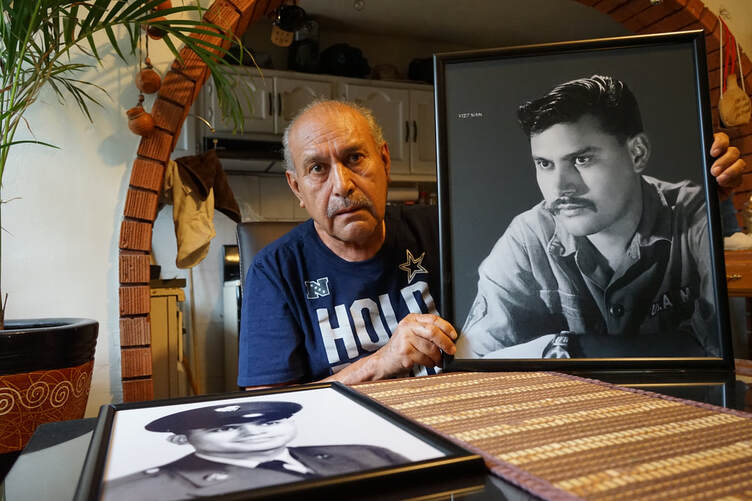

Panchito, a deported veteran raised in El Paso, Texas, drafted into the US Army during the Vietnam War, displays his boot camp and “in country” portraits.

Juarez, Mexico, 2019.

Juarez, Mexico, 2019.

|

Hilarion, US Army combat veteran from Trinidad and Tobago in a meeting room at New York University.

New York, New York, August 2019. |

"I know Mike," as he is known throughout Juarez, Mexico, on the Tinder dating app, is a deported US Marine Corps veteran making a living as a happy hour DJ in strip mall bars.

Juarez, Mexico, July 2019. |

US Marine Corps veteran Enrique Salas’s flag-draped casket outside St. Anthony's Church. Salas, 47, had a truck accident in Tijuana, Mexico, where he was living following his deportation. Hi fellow veterans fought to get a humanitarian visa to take him to San Diego, where he died.

Reedley, California, April 2018.

Reedley, California, April 2018.

|

Ricardo, US Army veteran.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2019. |

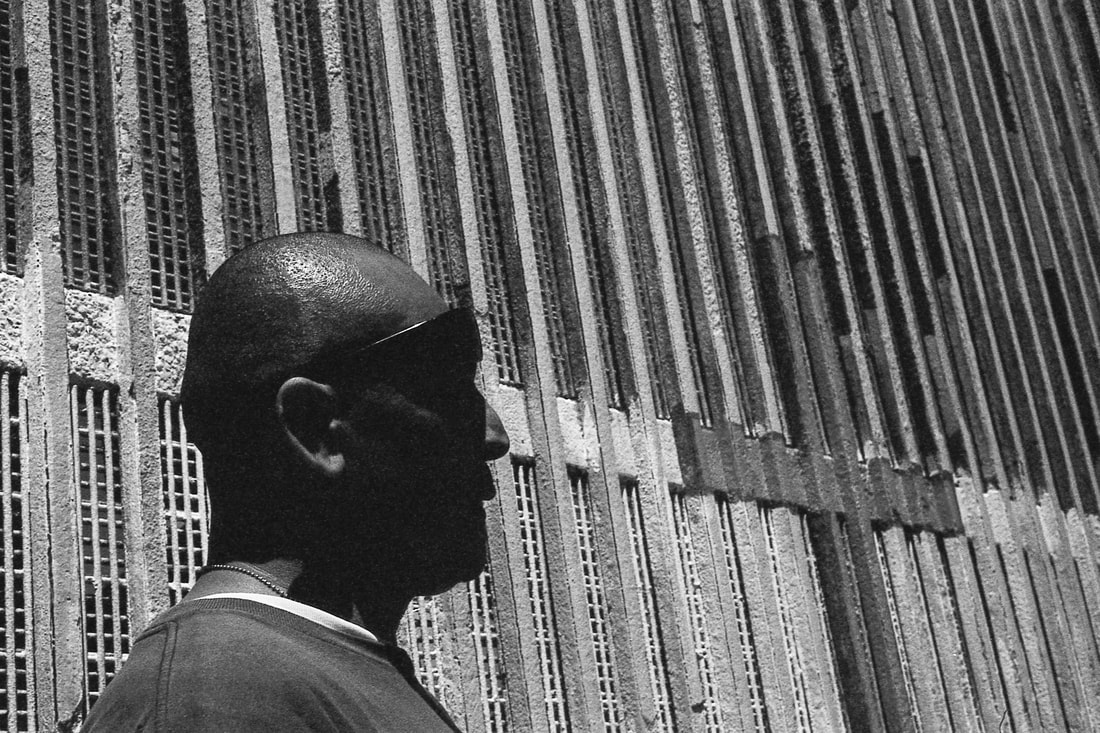

Carlos, US Marine Corps veteran.

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2018. |

Richard, US Marine Corps veteran.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2022. |

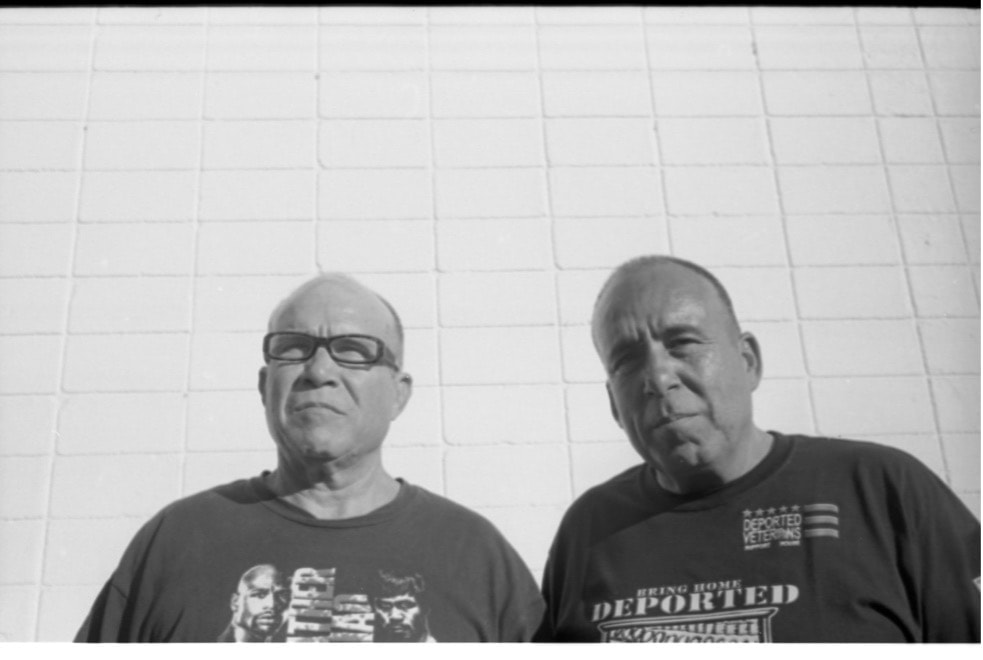

|

Brawley City Councilman and Marine Corps veteran Ramon Castro, on his 40-day walk along the US–Mexico border from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico to show solidarity with deported veterans.

El Paso, Texas, July 2021. |

ACLU staff attorney Sameer Ahmed with US Army veteran Yea Ji Sea as she waits to be sworn in as a US citizen at the Los Angeles Convention Center.

Los Angeles, August 2018. |

|

The refrigerator “medicine cabinet” of Ramon, US Air Force Vietnam War veteran, with VA Bronx Pharmacy prescriptions. Ramon goes to the VA five days a week for appointments and group therapy.

Bronx, New York, August 2019. |

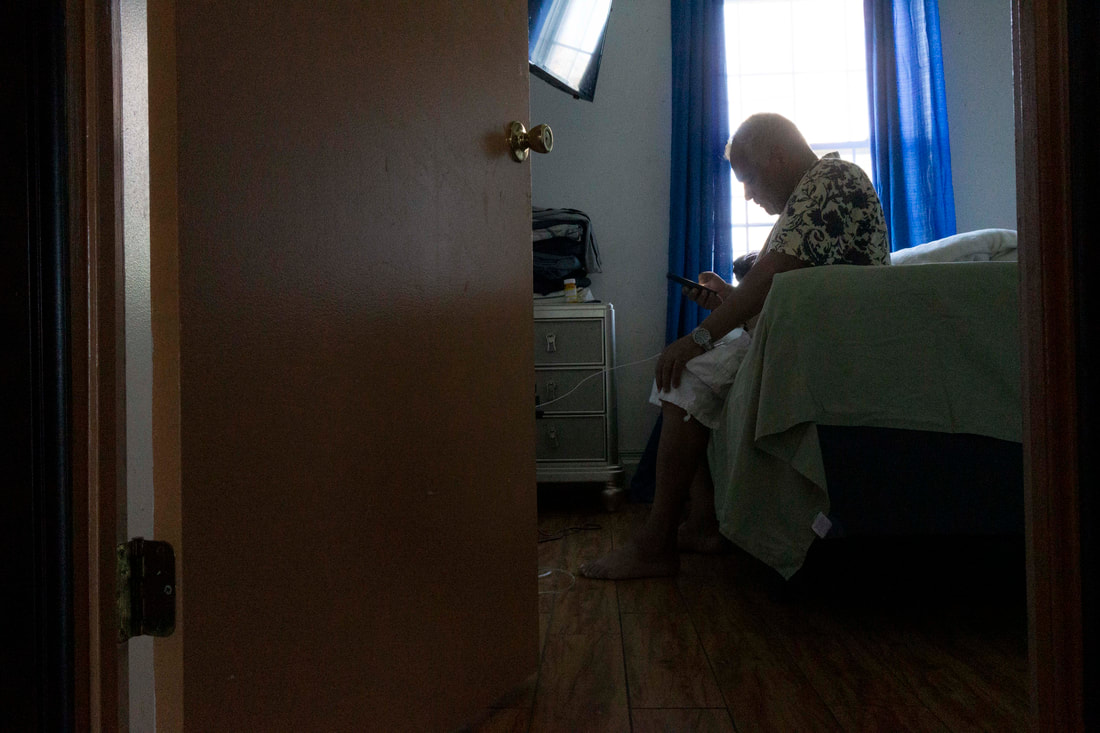

Ramon, US Air Force Vietnam War veteran, checking his upcoming VA appointments at the James J. Peters VA Medical Center. Ramon fears he will be deported.

Bronx, New York, August 2019. |

Joe, from Hollywood, California, and drafted into the US Army during the Vietnam War, on his first day of deportation.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2018.

Tijuana, Mexico, 2018.

|

Congressional visit by US Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois on Veterans Day. “I am ashamed of and heartbroken by how our nation is treating the deported veterans I met with today,” said the senator. “They are Americans all but on paper.”

Tijuana, Mexico, 2019. |

Repatriated US Army paratrooper Hector Barajas, flanked by deported US Marine Corps veterans Richard and Emiliano from Mexico and Armando from Panama, during a Congressional visit by veteran and US Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois on Veterans Day.

|

|

Ivy, US Army Iraq War veteran, sounding off in his home office.

Juarez, Mexico, July 2019. |

Rudi rides a double decker bus. He is a deported US Army veteran, born Udo Akermann in a women's prison in Aichach, Germany, to a Jewish mother and an African American father.

London, England, March 2020. |

|

Ms. Santos displays a US Army boot camp portrait of her deported son, Juan.

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, July 2018. |

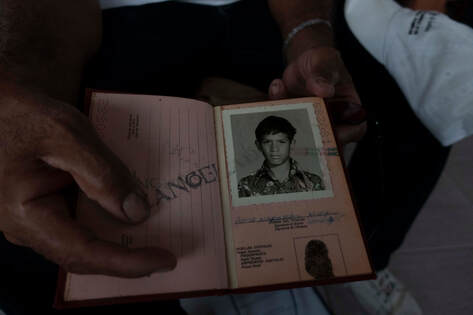

José, with a Dominican passport in hand, was raised in Washington Heights, New York. He joined the US Army with a group of friends after the Marine Barracks Bombing in Beirut, 1983.

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2018. |

California Congresswoman Nanette Barragán and deported veteran Hector Barajas speak with ABC 7 news on a Congressional visit to the “Bunker,” the Deported Veteran Support House.

Tijuana, Mexico, June 2017.

Tijuana, Mexico, June 2017.

A message from Jospeh Silva....

My name is Joseph Silva. I am a United States Navy veteran and a Documentary Fine Art photographer.

“You don’t leave your shipmate on the beach, leave no man behind.” - the Soldier's Creed.

As of 2021, I have shot a couple hundred rolls of film and filled multiple hard drives. I personally invested 6 years of my life to raising awareness of the deportation of Veterans from the United States Military. I have traveled to the Caribbean, Central America, Europe, and North America documenting deported Veterans. I spent extended time with these Veterans and their families so that I might share their story.

My journey started in the spring of 2016 while photographing Donald Trump protesters in downtown San Diego. I started to hear stories about deported veterans, so I sent a message to Hector Barajas, a US Army veteran deported to Tijuana, Mexico. I told him I wanted to cross the border to hear his story. A couple days later I took a Leica M4, M3, and a checked-out Canon 7D from the Santa Monica College student newspaper. I met Hector at the BUNKER, the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana, Mexico. After arriving at the BUNKER and meeting Hector and fellow Veterans, I felt like I was at a VRC (veteran resource center) on a college campus shooting the shit: telling sea stories, talking about deployments, hitting the beach, Tam’s Burgers, Okinawa, watching action films, true crime documentaries and Breaking Bad marathons on TV. I knew within 20 minutes after being in their presence that I had to tell their stories.

A year later, spring of 2017, I accompanied my new friend Hector to Juarez, Mexico to meet more deported veterans and help open a BUNKER, a Deported Veteran Support House. It has been one meeting after another. In Juarez, I met a deported female Marine through my uber driver. I spent 30 minutes with her and before parting ways, she told me that her little brother was an Air Force Veteran who was deported. We had a conference call and exchanged numbers and then she vanished into the night.

You may not be aware, but there are hundreds of deported veterans who were drafted during the Vietnam War only to be deported. There are even more deported Veterans from the many recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is unbelievable to think this could happen, but it has, and it continues. I believe anyone willing to volunteer for the United States military should automatically become a United States citizen, no discussion.

EXHIBITION VIDEO

EXHIBTION PODCAST: CSUN EMANCIPATED

Deported Veterans, a discussion on deportation of U.S. noncitizen service members and immigration....

In this episode, Marta Valier discusses deportations of immigrants from the U.S., more specifically about the deportation of veterans, with Héctor Barajas, director and founder of the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana, Mexico, ACLU immigration attorney Andrés Kwon, and photographer Joseph Silva, author of the photographic exhibition Deported Veterans at the Museum of Social Justice. Visit CSUN Tom and Ethel Bradley Center webpage to explore their Border Studies archive, and see some of the digitized images of the Julián Cardona Collection.

Listen to the podcast here.

In this episode, Marta Valier discusses deportations of immigrants from the U.S., more specifically about the deportation of veterans, with Héctor Barajas, director and founder of the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana, Mexico, ACLU immigration attorney Andrés Kwon, and photographer Joseph Silva, author of the photographic exhibition Deported Veterans at the Museum of Social Justice. Visit CSUN Tom and Ethel Bradley Center webpage to explore their Border Studies archive, and see some of the digitized images of the Julián Cardona Collection.

Listen to the podcast here.

EDUCATIONAL TOOL

RESOURCES

To stay current on the struggles of deported veterans follow these organizations.

- Deported Veterans Support House: Facebook @DeportedVeteransSupportHouse

- Border Angels: www.borderangels.org

- Immigrants Rising: www.immigrant rising.org/supportgroups

- ACLU of Southern California: www.aclusocal.org

- Immigrant Defenders Law Center: www.immdef.org

- Public Counsel: www.publiccounsel.org

NEWS COVERAGE

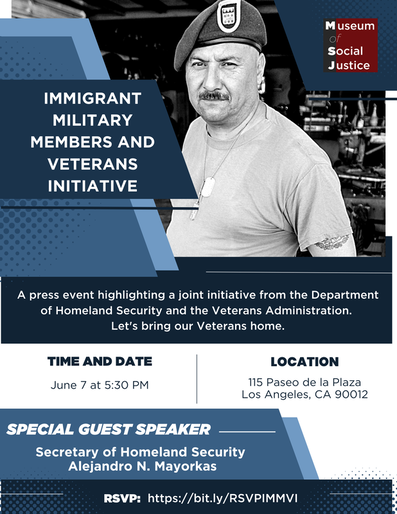

Immigrant Military Members Inititative Press Evenrt with Secretary Mayorkas

TELEMUNDO NOTICIAS

8 JUNIO 2022

El secretario de Seguridad Nacional, Alejandro Mayorkas, anunció una iniciativa para consolidar los recursos para los veteranos de guerra que han sido deportados. A los que sigan fuera de EE.UU. se les permitirá regresar. Video oficial de Noticias Telemundo.

The Secretary of Homeland Security, Alejandro Mayorkas, announced an initiative to consolidate resources for war veterans who have been deported. Those who remain outside the US will be allowed to return. Official video of Noticias Telemundo.

TELEMUNDO NOTICIAS

8 JUNIO 2022

El secretario de Seguridad Nacional, Alejandro Mayorkas, anunció una iniciativa para consolidar los recursos para los veteranos de guerra que han sido deportados. A los que sigan fuera de EE.UU. se les permitirá regresar. Video oficial de Noticias Telemundo.

The Secretary of Homeland Security, Alejandro Mayorkas, announced an initiative to consolidate resources for war veterans who have been deported. Those who remain outside the US will be allowed to return. Official video of Noticias Telemundo.

Museum of Social Justice: Joseph Silva: Deported Veterans

ANDY ROMANOFF, L'ŒIL DE LA PHOTOGRAPHIE

MAY 2, 2022

Los Angeles is a big city, five hundred square miles of endless neighborhoods seemingly without a center. Fifty years ago, new in town, I struggled to grasp this gigantic place without much success. One night I was telling this to a friend when he gave me a thought I still hold on to. The heart of Los Angeles, he told me, is a little plaza near downtown called El Pueblo de Los Angeles. It dates back to the earliest settlers and everything else is newer and radiates out from it. “Go and stand in the plaza,” he said, “close your eyes and you can feel the city all around you.” So I went, and stood with closed eyes and the feeling slowly grew in

me that I was standing at the calm center of the city. There may have been drugs involved that night but for me ever since, Olvera Street and the plaza down at the end have been the heart of L.A. Sitting here still calms me and resets my senses.

The Museum of Social Justice is located on the edge of the plaza, in a small space down some stairs at the corner of a large building, the United Methodist Church. The museum calls attention to often overlooked issues and right now it is calling attention to the immigrants who served in the United States military, risked their lives to keep us safe, but then later run afoul of the law. Unprotected by citizenship they have been thrown out of the country they fought

to protect.

Joseph Silva is a U.S. Navy Veteran and a Documentary Fine Art Photographer. He spent six years exploring this story, traveling to Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America and Europe to photograph the veterans this country has turned away. The Soldier’s Creed: “You don’t leave your shipmate on the beach, leave no man behind” drove him to tell the story. In his personal statement about the work Silva says, “My journey started in the spring of 2016 while photographing Donald Trump protesters in downtown San Diego. I started to hear stories about deported veterans, so I sent a message to Hector Barajas, a US Army veteran

deported to Tijuana, Mexico. I told him I wanted to cross the border to hear his story. A couple days later I took a Leica M4, M3, and a checked-out Canon 7D from the Santa 2/3 Monica College student newspaper. I met Hector at the BUNKER, the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana, Mexico. After arriving at the BUNKER and meeting Hector and fellow Veterans, I felt like I was at a VRC (veteran resource center) on a college campus shooting the shit …. I knew within 20 minutes after being in their presence that I had to tell their stories.”

Silva’s work fills hundreds of rolls of film and multiple hard drives and the pictures on display here attest to his vision and his passion. But the story he tells is a complex one, one that the photographs alone cannot reveal, so each picture is accompanied by a short text that gives you a name and a glimpse into the person pictured. The combination of words and pictures tells a sobering story. Moving slowly in the quiet room, seeing them and learning little bits

about these strangers, I found the pictures and text together illuminated their lives, and knowing their names brought them even closer.

For the record, this exhibit is not a simple one-dimensional story. Some of these soldiers have adapted to life in their new countries and would be happy just to come once in a while and visit friends and family left behind; others want the birthright they believe they have earned, but all feel that something is fundamentally wrong with the way they have been treated.

So once again, I found myself in the plaza at the at the heart of Los Angeles. This time I gained an understanding of a story I hadn’t thought about and saw an exhibition worth seeing. If you have the chance I suggest you come down here too. You can spend some time looking at Joseph Silva’s fine photos and then you can stand in the plaza at the center of Los Angeles, feel yourself in the middle of it all, and think for yourself about what ought to be done.

ANDY ROMANOFF, L'ŒIL DE LA PHOTOGRAPHIE

MAY 2, 2022

Los Angeles is a big city, five hundred square miles of endless neighborhoods seemingly without a center. Fifty years ago, new in town, I struggled to grasp this gigantic place without much success. One night I was telling this to a friend when he gave me a thought I still hold on to. The heart of Los Angeles, he told me, is a little plaza near downtown called El Pueblo de Los Angeles. It dates back to the earliest settlers and everything else is newer and radiates out from it. “Go and stand in the plaza,” he said, “close your eyes and you can feel the city all around you.” So I went, and stood with closed eyes and the feeling slowly grew in

me that I was standing at the calm center of the city. There may have been drugs involved that night but for me ever since, Olvera Street and the plaza down at the end have been the heart of L.A. Sitting here still calms me and resets my senses.

The Museum of Social Justice is located on the edge of the plaza, in a small space down some stairs at the corner of a large building, the United Methodist Church. The museum calls attention to often overlooked issues and right now it is calling attention to the immigrants who served in the United States military, risked their lives to keep us safe, but then later run afoul of the law. Unprotected by citizenship they have been thrown out of the country they fought

to protect.

Joseph Silva is a U.S. Navy Veteran and a Documentary Fine Art Photographer. He spent six years exploring this story, traveling to Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America and Europe to photograph the veterans this country has turned away. The Soldier’s Creed: “You don’t leave your shipmate on the beach, leave no man behind” drove him to tell the story. In his personal statement about the work Silva says, “My journey started in the spring of 2016 while photographing Donald Trump protesters in downtown San Diego. I started to hear stories about deported veterans, so I sent a message to Hector Barajas, a US Army veteran

deported to Tijuana, Mexico. I told him I wanted to cross the border to hear his story. A couple days later I took a Leica M4, M3, and a checked-out Canon 7D from the Santa 2/3 Monica College student newspaper. I met Hector at the BUNKER, the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana, Mexico. After arriving at the BUNKER and meeting Hector and fellow Veterans, I felt like I was at a VRC (veteran resource center) on a college campus shooting the shit …. I knew within 20 minutes after being in their presence that I had to tell their stories.”

Silva’s work fills hundreds of rolls of film and multiple hard drives and the pictures on display here attest to his vision and his passion. But the story he tells is a complex one, one that the photographs alone cannot reveal, so each picture is accompanied by a short text that gives you a name and a glimpse into the person pictured. The combination of words and pictures tells a sobering story. Moving slowly in the quiet room, seeing them and learning little bits

about these strangers, I found the pictures and text together illuminated their lives, and knowing their names brought them even closer.

For the record, this exhibit is not a simple one-dimensional story. Some of these soldiers have adapted to life in their new countries and would be happy just to come once in a while and visit friends and family left behind; others want the birthright they believe they have earned, but all feel that something is fundamentally wrong with the way they have been treated.

So once again, I found myself in the plaza at the at the heart of Los Angeles. This time I gained an understanding of a story I hadn’t thought about and saw an exhibition worth seeing. If you have the chance I suggest you come down here too. You can spend some time looking at Joseph Silva’s fine photos and then you can stand in the plaza at the center of Los Angeles, feel yourself in the middle of it all, and think for yourself about what ought to be done.

New photo exhibit puts spotlight on deported veterans

According to a new exhibit at the Museum of Social Justice, each year 5,000 new immigrants join the U.S. military.

SOPHIE FLAY, ABC7 SALUTES

MAR 14, 2022

Documentary photographer Joseph Silva has spent six years documenting people that he calls family.

"We have the same story. So, we can talk about similar things that we've done in the military or out of the military," said Silva.

His new exhibit called 'Deported Veterans' depicts just that. He gets to know veterans that have been deported and then asks to take their picture.

Silva is veteran himself.

"I joined the Navy right out of high school because I wanted to see the world," said Silva.

According to Silva, each year 5,000 new immigrants join the U.S. military.

"People automatically assume that you have to be a US citizen, to be a veteran, not true, you can be a green card holder, and join the US military."

He hopes this exhibit can help people understand that these men and women that have put their life on the line for our county, consider the U.S. home. Yet, they often don't get to stay here long after serving.

"These are men and women who served the United States military. And with this small crime or glitch in the system, they were disregarded. They were deported," said Silva.

According to a new exhibit at the Museum of Social Justice, each year 5,000 new immigrants join the U.S. military.

SOPHIE FLAY, ABC7 SALUTES

MAR 14, 2022

Documentary photographer Joseph Silva has spent six years documenting people that he calls family.

"We have the same story. So, we can talk about similar things that we've done in the military or out of the military," said Silva.

His new exhibit called 'Deported Veterans' depicts just that. He gets to know veterans that have been deported and then asks to take their picture.

Silva is veteran himself.

"I joined the Navy right out of high school because I wanted to see the world," said Silva.

According to Silva, each year 5,000 new immigrants join the U.S. military.

"People automatically assume that you have to be a US citizen, to be a veteran, not true, you can be a green card holder, and join the US military."

He hopes this exhibit can help people understand that these men and women that have put their life on the line for our county, consider the U.S. home. Yet, they often don't get to stay here long after serving.

"These are men and women who served the United States military. And with this small crime or glitch in the system, they were disregarded. They were deported," said Silva.

Photography Exhibition Showcases the Lives of Deported U.S. Veterans

MERCEDES CANNON, CARMEN RAMOS CHANDLER, CSUN TODAY

FEB 28, 2022

Serving your country is viewed as an honorable path for many Americans. But military service is often not enough to be considered a citizen on paper.

Veteran Joseph Silva, a California State University, Northridge alumnus and staff member of California State University, Northridge’s Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, exposes the lesser-known issue of veterans facing deportation in a photography exhibition which opened last week in downtown Los Angeles.

The exhibition, titled “Deported Veterans: Photographs by Joseph Silva,” was organized by the Museum of Social Justice and the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center and opened Thursday, Feb. 24, at the Museum of Social Justice, located at 115 Paseo de La Plaza, Los Angeles. It is the first of two shows featuring of Silva’s work on the subject of deported veterans. The second will be held later this year at CSUN in collaboration with the university’s DREAM and Veterans Resource centers.

“I invested six years of my life to raising awareness of the deportation of veterans from the United States military,” said Silva. “I spent extended time with these veterans and their families so that I might share their stories.”

Read the rest of the article here.

MERCEDES CANNON, CARMEN RAMOS CHANDLER, CSUN TODAY

FEB 28, 2022

Serving your country is viewed as an honorable path for many Americans. But military service is often not enough to be considered a citizen on paper.

Veteran Joseph Silva, a California State University, Northridge alumnus and staff member of California State University, Northridge’s Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, exposes the lesser-known issue of veterans facing deportation in a photography exhibition which opened last week in downtown Los Angeles.

The exhibition, titled “Deported Veterans: Photographs by Joseph Silva,” was organized by the Museum of Social Justice and the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center and opened Thursday, Feb. 24, at the Museum of Social Justice, located at 115 Paseo de La Plaza, Los Angeles. It is the first of two shows featuring of Silva’s work on the subject of deported veterans. The second will be held later this year at CSUN in collaboration with the university’s DREAM and Veterans Resource centers.

“I invested six years of my life to raising awareness of the deportation of veterans from the United States military,” said Silva. “I spent extended time with these veterans and their families so that I might share their stories.”

Read the rest of the article here.

Exhibición fotográfica crea conciencia sobre los veteranos deportados

BY ARACEIL MARTINEZ ORTEGA, LA OPINIÓN

DOMINGO 27 FEBRERO 2022

Cuando en 2015, Joseph Silva se enteró que habría una protesta de veteranos deportados en San Diego, se apuntó para unirse a la manifestación, sin imaginar que su participación daría pie a un proyecto que resultó en una exhibición fotográfica que se inaugura en Los Ángeles, y con la que planea recorrer el mundo.

“Le hablé a Héctor Barajas, – líder por los derechos de los veteranos deportados- , y le dije que si podía ir a la protesta. Me dijo que sí y me fui de Los Ángeles a San Diego”.

Fotógrafo de profesión, Silva comenzó a hacer retratos de los veteranos deportados y cuando se dio cuenta ya tenía por lo menos 50.

Completé un par de cientos de rollos de película y llené varios discos duros”, dice.

“Invertí 6 años de mi vida para crear conciencia sobre la deportación de veteranos de las fuerzas armadas de Estados Unidos. Pasé mucho tiempo con ellos y sus familias con el propósito de compartir sus historias”.

La exhibición “Deported Veterans: Photographs by Joseph Silva” (en español Veteranos Deportados: Fotografías de Joseph Silva) estará en el Museo de Justicia Social desde el 24 de febrero hasta el 17 de julio.

“Tengo fotografías de veteranos deportados a México, Haití, República Dominicana, Panamá, Belice, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Alemania, Suiza y África”.

Read the rest of the article here.

BY ARACEIL MARTINEZ ORTEGA, LA OPINIÓN

DOMINGO 27 FEBRERO 2022

Cuando en 2015, Joseph Silva se enteró que habría una protesta de veteranos deportados en San Diego, se apuntó para unirse a la manifestación, sin imaginar que su participación daría pie a un proyecto que resultó en una exhibición fotográfica que se inaugura en Los Ángeles, y con la que planea recorrer el mundo.

“Le hablé a Héctor Barajas, – líder por los derechos de los veteranos deportados- , y le dije que si podía ir a la protesta. Me dijo que sí y me fui de Los Ángeles a San Diego”.

Fotógrafo de profesión, Silva comenzó a hacer retratos de los veteranos deportados y cuando se dio cuenta ya tenía por lo menos 50.

Completé un par de cientos de rollos de película y llené varios discos duros”, dice.

“Invertí 6 años de mi vida para crear conciencia sobre la deportación de veteranos de las fuerzas armadas de Estados Unidos. Pasé mucho tiempo con ellos y sus familias con el propósito de compartir sus historias”.

La exhibición “Deported Veterans: Photographs by Joseph Silva” (en español Veteranos Deportados: Fotografías de Joseph Silva) estará en el Museo de Justicia Social desde el 24 de febrero hasta el 17 de julio.

“Tengo fotografías de veteranos deportados a México, Haití, República Dominicana, Panamá, Belice, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Alemania, Suiza y África”.

Read the rest of the article here.

Army vet reunited with mom on Valentine's Day after 10-year deportation

ROBERT SHERMAN, KATIE SMITH, NEWS NATION

FEB 14, 2022

SAN DIEGO, Calif. (NewsNation Now) — In the early hours of Valentine’s Day, Mauricio Hernandez-Mata crossed into the United States from Mexico at the San Ysidro Port of Entry in California, marking the Army veteran’s first return into the country since he was deported more than 10 years ago.

“I think I’m gonna wake up right now and I’m still gonna be in Mexico deported,” he said. “It’s unreal.”

Hernandez-Mata served in more than 100 combat missions for the U.S. Army and when he left the service, he expected to be granted U.S. citizenship. Instead, he was deported after being convicted of drug and firearm possession.

"Exiled is, in my opinion, a kind word for the feeling," he told NewsNation at the nation's busiest border crossing where tens of thousands of people enter the country each day.

Hernandez-Mata's attorney Andres Kwon, of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said immigration laws can be "unforgiving."

"They're extremely harsh," Kwon said. "Things that are misdemeanors can be deemed in immigration law as an aggravated felony."

It's not uncommon for veterans like Hernandez-Mata, who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, to take actions that result in deportation, despite their military status, Kwon said.

A U.S. Government Accountability Office report found that between the years of 2013 and 2018, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement deported 92 of the 250 veterans to whom they issued a notice to appear (a document that begins deportation proceedings). Veteran Affairs benefits aren't fully accessible to veterans who live outside of the U.S.

According to the government report, the most common countries of origin for deported veterans are:

"If I had a second chance I would gladly do it all again – fight for my country in any conflict," Hernandez-Mata said. "I have always considered myself and I am an American."

ROBERT SHERMAN, KATIE SMITH, NEWS NATION

FEB 14, 2022

SAN DIEGO, Calif. (NewsNation Now) — In the early hours of Valentine’s Day, Mauricio Hernandez-Mata crossed into the United States from Mexico at the San Ysidro Port of Entry in California, marking the Army veteran’s first return into the country since he was deported more than 10 years ago.

“I think I’m gonna wake up right now and I’m still gonna be in Mexico deported,” he said. “It’s unreal.”

Hernandez-Mata served in more than 100 combat missions for the U.S. Army and when he left the service, he expected to be granted U.S. citizenship. Instead, he was deported after being convicted of drug and firearm possession.

"Exiled is, in my opinion, a kind word for the feeling," he told NewsNation at the nation's busiest border crossing where tens of thousands of people enter the country each day.

Hernandez-Mata's attorney Andres Kwon, of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said immigration laws can be "unforgiving."

"They're extremely harsh," Kwon said. "Things that are misdemeanors can be deemed in immigration law as an aggravated felony."

It's not uncommon for veterans like Hernandez-Mata, who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, to take actions that result in deportation, despite their military status, Kwon said.

A U.S. Government Accountability Office report found that between the years of 2013 and 2018, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement deported 92 of the 250 veterans to whom they issued a notice to appear (a document that begins deportation proceedings). Veteran Affairs benefits aren't fully accessible to veterans who live outside of the U.S.

According to the government report, the most common countries of origin for deported veterans are:

- Mexico

- Germany

- Belize

- Canada

- Dominican Republic

- Federated States of Micronesia

- U.K.

- Philippines

- Thailand

- Costa Rica

- Korea

- Poland

"If I had a second chance I would gladly do it all again – fight for my country in any conflict," Hernandez-Mata said. "I have always considered myself and I am an American."

EVENTS

Immigrant Military Members and Veterans Initiative Press Event with Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro N. Mayorkas

On June 7, 2022, the Museum hosted a press event highlighting the joint initiative from the Department of Homeland Security and the Veterans Administration with Secretary Mayorkas. The Secretary met with veterans in a private meeting before the event, where veterans discussed their concerns and stressed how important it is to repatriate veterans back to the United States and prevent their deportation from happening in the future. Afterward, the Secretary joined the Secretary in viewing the exhibition Deported Veterans: Photographs by Joseph Silva, met with family members, and shared a few words with guests. The Museum wants to thank the ACLU of Southern California, Public Counsel, Immigrant Defenders, and community partners and advocates for making the Immigrant Military Members and Veterans Initiative press event a reality, as well as the Department of Homeland Security. The Museum especially wants to thank the Veterans for sharing their stories and service. Let’s bring our veterans home!

Photogrpahs by ©Roger Alcocer

Photogrpahs by ©Roger Alcocer

The DHS-VA Military Members and Veterans Initiative (IMMVI) visited the Museum to view the exhibition on March 21, 2022.

From left to right: Andres Kwon, ACLU SoCal, Debra Roger, Deputy Associate Director, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Safi Khan, Special Assistant (Attorney), US Department of Veterans Affairs, Joseph Silva, exhibition photographer, Hector Barajas, Deported Veterans Support House, Jenni Pasquarella, ACLU SoCal, José Luis Benavides, director of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, CSUN, Salomon Loayza, repatriated veteran, and Xóchitl Rodriguez Murillo, Deputy Secretary, Minority & Underrepresented Veterans, Cal Vet, and Carrie Anderson, Director of Policy, Family Reunification Task Force, U.S. Department of Homeland Security.